「說我在考驗極限的話,真是太低估我了;」艾未未說,他續解釋:「我只是在行使憲法賦予的權力。」

昨晚看過紀錄觀點【艾未未發課案】,對於言論審查和攝影監視,有沒有一番思考?反觀諸己,我們的自由得來不易,也還有很多進步空間喏。不過,也是因為相對的自由,公視紀錄觀點才能每每帶給大家各種好片啊!

關於艾未未的紀錄片還有【艾未未草泥馬 Ai Wei Wei: Never Sorry】、【艾未未:公平 Ai Wei Wei: Without Fear or Favor】。大家可以參考看看~

★2012 台灣國際紀錄片雙年展【艾未未草泥馬】預告:https://youtu.be/HX0bcYD4dNY

★BBC【艾未未:公平 Ai Wei Wei: Without Fear or Favor】全片:https://youtu.be/gcRodOfu_s8

★【艾未未發課案】影片簡介: http://viewpoint.pts.org.tw/?p=4524

★BBC【艾未未:公平 Ai Wei Wei: Without Fear or Favor】全片:https://youtu.be/gcRodOfu_s8

★【艾未未發課案】影片簡介: http://viewpoint.pts.org.tw/?p=4524

艾未未:“政府已徹底失去基本原則”

丹麥導演約翰森拍攝的紀錄片《艾未未發課案》英文版本周正式公映。艾未未接受美聯社專訪時批評說,中國政府已徹底失去基本原則,而且使用不正當手段壓制異議人士。

(德國之聲中文網)艾未未的支持者認為,他2011年被中國稅務機關要求交付240萬美元的未繳稅款和罰款是因為他的直言和其參與的活動。艾未未批評指出,在稅案一事中,他的中國藝術家同行沒有為其發聲。他在其北京工作室近日接受美聯社專訪時表示,但是他對中國的年輕一代持樂觀態度。

他在談及丹麥導演安德烈亞斯•約翰森(Andreas Johnsen)拍攝的《 艾未未發課案》(Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case)時表示:"以前,我天真地認為一個政權、一個強大的社會永遠不會在法律案件中使用卑鄙的手段。如果要以某項罪名控告某人,必須走正常程序,不可能誣陷這個人和使其噤聲。"

艾未未指出,中國領導人經常宣稱中共黨員是誠實守信、光明磊落的人。"但我們今天看到,(政府)已徹底失去基本原則。"

長達86分鐘的《艾未未發課案》以2011年艾未未在被羈押81天后獲釋、被記者包圍的場景作為開頭。艾未未是一名常年批評政府的活動人士。"阿拉伯春天"後,他因為和其他異議人士一起呼籲中國進行社會和政治改革而被拘留,最後被無罪釋放。

當局" 依照自己的需要製定法律"

2011年艾未未被羈押81天后獲釋後,受到媒體廣泛關注

艾未未獲釋後,在一次閉門聽證會上,中國當局要求其所在的北京發課文化公司支付240萬美元的未繳稅款和罰款。艾未未對此提出上訴,結果以 敗訴告終。

因政治異見而獲罪會引起國際社會譴責,因此近來,中國當局愈加頻繁地以"尋釁滋事"或商業犯罪等非政治罪名控告異議人士及其親屬。去年,諾貝爾和平獎得主劉曉波的妻弟劉暉以"詐騙罪"被判處有期徒刑11年。

從年輕的時候開始,艾未未就敢於用藝術和評論表達自己的觀點,這一點可能是遺傳了他的父親--一名敢於挑戰權威的著名詩人。艾未未曾在其攝影作品中對天安門豎起中指。

2005年,艾未未開始在社交媒體上發表措辭嚴厲的評論,直到2009年他的微博賬號被關閉。尤其使當局不滿的是他發起"公民調查"要求公開08年四川地震中因校舍豆腐渣工程死難孩童的真實數字。

"政府無法壓制他們所有人"

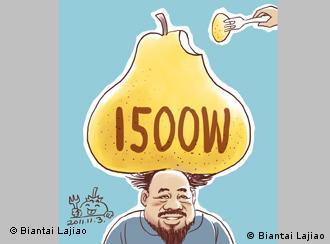

網民變態辣椒就"艾未未稅案"所作的漫畫

今年57歲的艾未未說,他沒有刻意成為一名藝術家。"我的所有感覺和觀點都是真實的。這些都是我作為個人或者是一名和藝術有關的人一般會有的觀點。"他繼續說:"但是因為不斷的遭受打壓和被禁,我才成了一個不同尋常的人,我也因此成為所謂的活動人士。"

他的遭遇受到海外媒體的詳細報導,他也因此在國際上聲名遠揚。艾未未說他對外國藝術家和組織的支持表示感謝。他也表示對中國藝術家的漠不關心感到沮喪。"我受到的最大心靈創傷不是我在獄中的遭遇,而是我在(稅案)中看到中國藝術家作為一群人假裝什麼也沒有發生。"他補充說:"他們現在依舊會在拍賣會和國際藝術市場上為一些贗品叫好,但是卻對這個社會以及對同行中的個人遭遇漠不關心。這是在其他社會不可能發生的現象。"

艾未未表示相信追求自由和幸福的人最終會取得勝利。"我也許低估了自己。從政府對待我的方式來看,我確實與眾不同。每天都會有年輕人想和我握手、拍照和要簽名。他們敢於表達支持的聲音。"

當艾未未三年前接到巨額罰單時,近3萬人在網上表達了他們的支持,並進行募捐和借款,總額超過900萬元。《艾未未發課案》中可以看到,塞了錢的紙飛機飛進他的工作室。他的罰單現已付清。艾未未說:"政府無法壓制他們所有人,他 們都是普通人。"觀眾本週起可在 影片官網付費觀看該片。

aj/yr(AP)

DW.DE

完整報導 http://share.flog.cc/post/81906425779口述的逐字稿:...

艾未未單曲「傻伯夷」 出口成髒諷中國政府

「傻伯夷」MV全長5分13 秒,內容主要描述艾未未曾遭中國政府非法囚禁81天的遭遇,並以中國公安掀開艾未未的「疑犯」頭套畫面、被拍照偵訊開場,其他畫面包括艾未未無論走到哪, 即使洗澡,都有公安或武警在旁監視,以及在片尾由兒子操刀剃掉頭髮與招牌大鬍子,甚至穿女裝塗口紅。

此外,部分MV畫面呈現粗口諧音,包括 馬桶裡有河蟹與金魚,以及曾被艾未未拿來合拍裸照的草泥馬玩偶,甚至還出現充氣娃娃。河蟹是「和諧」的諧音,是中國網民用來諷刺官方控制輿論、創造「河蟹 社會」時的用語。曲名傻伯夷本身就是罵人是白痴、笨蛋的「傻逼」諧音,曲末甚至棄用傻伯夷,直接大唱傻逼。

該MV上傳網路後反應熱烈,有人大呼該MV「太給力」、創造出「和政治緊密關聯的美學」,以及「完美詮釋草泥馬精神」等。但也有人批評艾未未歌喉欠佳,而艾未未本人也坦承,自己唱得不好。中國微博上有關「傻伯夷」MV的討論已遭刪除,但YouTube上仍可見到回應。

艾未未受訪時表示,「傻伯夷」這首歌與MV,是為那些沒機會發出聲音的中國政治犯而唱與拍攝,他也希望透過這支MV,讓外界更關注中國缺乏法治的情況。

//////

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PizQCCHpIbY

歌词: 当你要出击,他嘟囔非暴力, 你拧他的耳朵,他说这样不治拉稀。 你说你马勒隔壁,他说他天下无敌。

你说你马勒隔壁,他说他天下无敌。 宽恕你大爷,容忍你妈逼, 素质你妹耶,至贱则无敌。 宽恕你大爷,容忍你妈逼, 素质你妹耶,至贱则无敌。

傻伯夷啊傻伯夷,傻伯夷啊傻伯夷, 傻伯夷啊傻伯夷,傻伯夷啊傻伯夷, 啦啦啦啦啦,啦啦啦啦啦。啦啦啦啦啦,啦啦啦啦啦。

啦啦啦啦啦,啦啦啦啦啦。啦啦啦啦啦,啦啦啦啦啦。 像一个傻逼一样站出来,国家就是一只鸡啊 菊花开遍原野,哪哪儿都是傻逼。

菊花开遍原野,哪哪儿啊都是傻逼。 宽恕你大爷,容忍你妈逼, 素质你妹耶,至贱则无敌。 你说你马勒隔壁,他说他天下无敌。

你说你马勒隔壁,他说他天下无敌。 菊花开遍原野,哪哪儿都是傻逼。 菊花开遍原野,哪哪儿啊都是傻逼。

·

訪談

艾未未訪談:沒什麼好隱瞞的,卻總在注視之下

報道 2013年02月28日

Sundance Selects

紀錄片《艾未未:道歉你妹》(Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry)中的一個場景,該片拍攝的是這位藝術家在2008年到2011年這段時期的狀態。

中國概念藝術家、雕塑家、攝影家和電影製作人艾未未的公司有個搞笑的名字——“發課設計公司”(Fake Design),但是他所面臨的挑戰卻是非常真實的。作為中國最為直言不諱的持不同政見者之一,他曾遭到拘留、逮捕和毆打,並且在實現中國憲法規定理應神聖不可侵犯的權利時,經常遭到騷擾和審查。《艾未未:道歉你妹》(Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry)這部紀錄片由美國導演艾莉森·克雷曼(Alison Klayman) 拍攝,它近距離審視了艾未未的藝術與政治活動,並展示出二者如何變得愈來愈難解難分。這部紀錄片將於周一晚上在PBS電視台播出,作為“獨立鏡頭” (Independent Lens)系列片的一部分(詳見當地放映表),該片主要集中在2008到2011年這段時間。該片去年夏天發行後受到評論界的好評,還在聖丹斯等電影節上 獲獎。

上周艾未未在北京的工作室內以英文接受了電話採訪,談了自己的藝術與政治活動,以及在紐約的歲月帶給他的影響。下面是採訪節選。

問:《道歉你妹》在2011年結束,當時你剛剛結束81天的秘密監禁,被羈押在家中。那麼你的現狀如何呢?

答:我現在應該說是個自由人了,但他們從沒歸還我的護照,所以不能出國。在中國,我周圍的環境寬鬆了很多,但我仍被密切監視着。如果我出門,仍然有人秘密監視我。

問:在那部影片里,你去接近那些被派來尾隨你的國家安全機關的盯梢者,試圖和他們交談。為什麼要這樣做?

答:我一直都覺得我們沒什麼可隱瞞的,所以我希望他們知道這一點。一般來說,被尾隨的人都會覺得受到威脅,感到 很害怕。所以我總是說:“如果你想找我,我們可以坐下來談談。你們甚至可以來我的辦公室,我會給你們一張桌子。你們可以看看我見了什麼人,如果我出門旅 行,我可以說你們是我的助手,所以不管我見到什麼人,你們也能見到什麼人。所以告訴你們老闆,這是個好機會,可以好好觀察一下這個被稱為顛覆政權者的危險 傢伙。”

問:類似這種對峙,以及你所做的其他各種事情,在西方被視為一種行為藝術。這個描述準確嗎?

答:我不想說這是一種行為藝術。這是一種表達,但不是設計好的表演。這很危險,很令人沮喪,是真實的生活。這是 一種生存方式,是在向那些人表明你自己。因為你不想讓他們覺得你被嚇壞了。大多數人都會選擇放棄,這會讓權力覺得自己強大無比,不可動搖。我想告訴做事的 人或者年輕人:你們可以堅持自己的權利。

問:所以在這樣的時刻,你覺得自己主要是一個藝術家還是一個政治活動家呢?

答:這兩個角色我都沒有刻意去扮演,或者說沒有刻意去想。我的生活非常豐富,由我自己主導,我有各種政治和社會 關懷,還要搞很多所謂文化和藝術活動。它們彼此密不可分,這對我來說一直都是必不可少的。就像你走路的同時還要呼吸,但你不一定非要注意到自己在呼吸。但 當你在非常困難的條件下走路,比如說爬山的時候,你會注意到自己必須拚命呼吸才行。所以我的活動多少有點像這種情況。

問:現在你的生活經常處於監視之下,為什麼又讓艾莉森·克雷曼拍這部片子呢?這不是更多的打擾嗎?

答:我覺得表現這種日常狀態是非常重要的,因為當人們想到中國,他們會覺得中國現在又強大又富裕。但他們必須知道在這個發展階段中有多少犧牲。有太多悲慘的不公正事件發生了。這個黨只是不去和你討論和談判這些問題。

所以這部影片非常重要,它向人展示了權力的存在。他們非常強大,但有時候也極度軟弱,他們其實無法承受任何抵抗或質疑的態度。

問:中國最近進行了領導人的更替,你對共產黨新的領導人有什麼看法,他們會放鬆這樣嚴密的控制嗎?

答:我看不到什麼新鮮的東西。不管洗多少次牌,拿牌的還是同一隻手。這就是他們的玩法。他們從不遵守規則,從不尊重他們自己的憲法。他們的權力從來 不受到任何真正的限制。沒有言論自由,沒有司法系統的獨立。一切還差得太遠,他們要做任何改變都很困難。我對改變不抱任何希望。

問:在那部影片展示你是社交網絡的積極使用者,既把它當做藝術工具也當成政治工具,你現在還能使用社交網絡嗎?

答:它是一個工具,但只在海外有效。中國的社交網絡上,我的名字都是被禁止的。這太具有象徵意義了。你可以看到整個世界都在努力建立快速的信息流, 但在中國,他們還在努力設置各種限制,想讓信息的傳播慢下來,或者阻撓它,這樣他們的年輕人成長中就永遠不會知道外面發生了什麼,永遠都不知道真正的挑 戰。我覺得他們設立國家網絡防火牆,實際上是為了維護他們自己的權力,犧牲了整個一代人的未來。 問:你提到個人與國家權力的關係這個話題。看了這部電影,我覺得你住在紐約那段時間就開始系統思考這個問題了。

答:是的,沒錯。我剛到紐約時,看到基本的社會公正是如何落實的,以及在很多情況下,又是怎樣沒能落實。我想了很多,我也參與過湯普金斯廣場公園暴動(Tompkins Square Park riots)和艾滋示威遊行,甚至還參加過反戰遊行。我經常說,我看過伊朗門事件(Iran-contra)聽證會,每一分鐘都沒落下。所以我一直都對正義在每個具體實例中如何實現這個過程非常感興趣。這對我一直有很大的吸引力。

問:在紐約的日子一直對你的創作有影響,那段時間是怎樣把你塑造成一個藝術家的?

答:那段時間非常重要。它給了我一個機會,讓我明白藝術是怎樣與現實生活,乃至我們的態度和生活方式發生關係。我覺得這些東西不應當分割開來。我覺得那些試圖把藝術與現實割裂開的藝術我都不會真正感興趣。這也是給我上了一課。

A Word With: Ai Weiwei

He May Have Nothing to Hide, but He’s Always Under Watch

February 28, 2013

The Chinese conceptual artist, sculptor, photographer and filmmaker Ai Weiwei has a company that bears the tongue-in-cheek name Fake Design, but the challenges he faces are all too real. As one of China’s most outspoken political dissidents he has been detained, arrested, beaten and repeatedly harassed and censored while trying to exercise rights supposedly enshrined in China’s constitution.

In “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry” the American filmmaker Alison Klayman offers a close-up look at Mr. Ai’s artistic and political activities and shows how they have become increasingly intertwined. Her documentary, which will be broadcast on Monday night on PBS stations as part of the “Independent Lens” series (check local listings), focuses on the period from 2008 to 2011. It had a critically praised commercial release last summer, after winning awards at Sundance and other film festivals.

Mr. Ai, 55, is the son of a renowned poet, Ai Qing, but he grew up in political disfavor. Following the Cultural Revolution he attended film school and then spent more than a decade in New York, returning to China in 1993 and quickly becoming a leader of an avant-garde movement. Though hired as the creative consultant for the design of the Bird’s Nest stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he had broken with the government by that year, criticizing both the staging of the Olympics as a “pretend smile” and the state’s handling of a devastating earthquake in Sichuan.

Last week Mr. Ai, speaking in English by phone from his studio in Beijing, discussed his artistic and political activities, including the effects of his years in New York. Here are excerpts from the conversation.

Q. “Never Sorry” ends in 2011, after you emerged from 81 days of secret detention and were placed under house arrest. How would you describe your current situation?

A. My status is supposed to be that of a free man, but they have never given back to me my passport. So I cannot travel abroad. Within China the conditions are much looser towards me, except that I am heavily monitored. If I go out, people still secretly monitor me.

Q. The movie shows you approaching state security surveillance agents assigned to tail you and trying to talk with them. Why do that?

A. I always think we have nothing to hide, so I want them to know that. Normally people, when they are being followed, are being intimidated or they are scared. So I always say: “If you are looking for me, we can sit down to talk. You can even come to my office, I’ll just give you a table. You’ll see whoever I see, and if I travel, I will name you as my assistant, so whoever I meet, you will also meet. So tell your boss that this is an opportunity to get a close look at this very dangerous guy named as a subversive of state power.”

Q. Here in the West confrontations like that, just like everything else you do, are seen as a type of performance art. Is this an accurate assessment?

A. I wouldn’t say it’s a form of performance art. It is expression, but not one designed for a show. It’s dangerous, it’s very frustrating, and it’s real life. It’s a way to survive, and it’s a way to announce yourself to those people. Because you don’t want them to look at you as scared. Most people would just give up, and that makes the power unshakably strong. I’m trying to tell the workers or the young people you can insist on your own rights.

Q. So at this juncture do you consider yourself to be primarily an artist or a political activist?

A. I’m not very conscious of or think about either position. I lead my life, which is quite dense, with all kinds of political and social concerns and a lot of so-called cultural or art activities. They integrate with each other, that’s always kind of necessary for me. It’s like when you walk, you breathe, but you’re not necessarily concerned about breathing. But when you walk under difficult conditions, like climbing a mountain, then you realize you have to catch your breath. So my activities are more or less like that.

Q. With your life under constant surveillance why did you allow Alison Klayman such access? Isn’t that one more intrusion?

A. I think it’s very important to address this kind of daily situation, because when people think about China, they think that China is so rich and powerful now. But they have to understand how much sacrifice went into the development of this stage. So many unfortunate injustices have happened. The party simply doesn’t discuss or negotiate with you.

So the film becomes important, to reveal power. They are so powerful, but sometimes they are extremely fragile, they cannot really take any kind of resistant attitude or questioning.

Q. China has recently had a change of leadership. What is your opinion of the new Communist Party leaders and the possibility that they might loosen that tight grip?

A. I don’t see anything new. No matter how many times you shuffle the deck, you still get the same old hand. It’s the way they play. They never follow the rules, they never respect their own Constitution. They never really have any kind of restrictions on power. There’s no freedom of speech, no independence for the judicial system. It’s so far behind, and it’s so difficult for them to make any kind of move. I’m not at all hopeful of change.

Q. In the film you are portrayed as a big user of social media, as both an artistic and political tool. Are you still able to use social media?

A. It’s a tool, but it only works abroad. Inside China with social media you cannot even type my name. It’s so symbolic. You see the whole world is trying to establish a fast flow of information. But in China they try to set up all kinds of obstacles, trying to make it slower or to block it, with their young people growing up never knowing what is going on outside, never knowing the real challenge. I think that by setting up this Great Firewall they really sacrifice a generation’s future for their own power.

Q. You have mentioned the issue of the individual in relation to state power. I get the impression from the film that it was while you were living in New York that you first started to think systematically about that.

A. Yes, that’s absolutely true. When I came to New York, I saw a kind of basic social justice, how it applies, or in many cases doesn’t apply. I did so much thinking, and I was also involved in the Tompkins Square Park riots or the AIDS demonstrations or even the antiwar demonstrations. I always say that I watched the Iran-contra hearings, every minute of that. So I am always interested in the process, in how justice is applied to each case. That is always fascinating to me.

Q. And in terms of a lasting impact on your creativity, how did your years in New York shape you as an artist?

A. They were extremely important. They gave me a chance to understand how art relates to real life and our attitudes and our lifestyle. I think they never should be separated. I think whoever is trying to separate it, in this kind of art I am never really interested. So that was a lesson too.

幽默的抗爭者艾未未

紀思道 2013年01月01日

北京

中國官方嘗試過授予艾未未榮譽,用顯赫的地位來買通他。他們也嘗試過把他投進監獄、對他進行罰款、並用棍棒狠狠地打他,以至於他需要接受緊急腦部手術。他們在絕望之中還曾懇求艾未未不要搗亂——但全都沒用。

像艾未未這樣有着全球大批追隨者的巨星級藝術家,中共中央政治局能把他怎麼樣呢?他製作了一段自己戴着手銬跳《江南style》的視頻,以嘲弄中國的體制,這段視頻很快在YouTube上獲得了100多萬點擊量。

當艾未未發佈了自己的一張裸照,把毛絨玩具當成遮羞布,用“草泥馬檔中央”諧音中文裡一句對中共中央的咒罵(更準確地說,是一句國罵)。而中共中央委員會又該做出何種反應呢?

比起被譴責,中國共產黨更厭惡的是被嘲笑,而幽默正是艾未未攻擊中共的代表性風格。其他異見人士如身在監獄的諾貝爾和平獎獲得者劉曉波,寫了大量有 關民主的雄辯文章,卻幾乎沒有吸引到普通的中國民眾。艾未未的藝術作品對很多人來說似乎也是無法理解的,但像草泥馬這樣的粗俗笑話能引起更多關注——也很 難被鎮壓。

“我覺得他們不知道怎樣對付像我這樣的人,”艾未未在接受採訪時說。“他們好像已經放棄管我了。”

中國共產黨面臨的一大麻煩是,55歲的艾未未是世界上最著名的藝術家之一。他的出身也和共產黨的革命戰爭緊密相連,其父母曾和中國新一屆最高領導人習近平的父母關係友好。

作為反抗政權的標誌性人物,艾未未的出現代表着中國的進步,反映出非官方的多元化正在興起。中國越來越讓我想起20世紀80年代早期的韓國和台灣,當時,受過教育的中產階級也是這樣開始一點一點地瓦解獨裁政權。

艾未未承認,中國確實出現了進步,他還說,他預計中國能在2020年之前實現民主——但他悲嘆現在已經太遲了。“他們已經浪費了整整一代的年輕人,”他說。

艾未未曾在紐約生活過十幾年,逐漸確立了他的藝術聲譽,而他的叛逆個性似乎也是在那些年中形成的。他在1993年回國,當時他36歲。最初他在政治上循規蹈矩,並參與了2008年北京奧運會宏偉的鳥巢體育場的設計。

2008年發生在西南省份四川省的大地震是讓他發生改變的一個因素。當時,許多校舍倒塌,學生家長抗議建築質量低劣,遭到了政府鎮壓。艾未未支持這些家長,開始要求政府更加公開。

他的對抗姿態惹怒了當局,他們毆打他,並強拆了他在上海的工作室。去年,政府又將他關押了近三個月。

當局仍禁止他出國,因此他無法出席自己正在華盛頓史密森尼博物館體系的赫什霍恩博物館(Hirshhorn Museum)舉行的藝術展。

這種壓力讓艾未未比以往任何時候都更強烈地感覺到,中國最大的問題之一便是專制政府。他不但沒有變得有所收斂,反而言論更加大膽。

“每一步,我都是被他們逼的,”他說。“我告訴他們,‘是你們創造了像我這樣的人。’”

出獄後,艾未未曾短暫地保持低調了一段時間,但隨後又恢復了他的政治惡作劇。為了監視他的舉動,當局在其工作室安裝了15個攝像頭。為了表示對此舉 的嘲弄,艾未未在互聯網上開設了名為“圍觀草場地”(weiweicam)的網站,播放從自己卧室傳出的畫面,這樣政府就能更密切地監視他了。

“他們幾乎是來求我把攝像頭關了,”他咧嘴笑着說。

我和他聊了很久。交談結束時,我問艾未未有沒有其他要說的。

“中國仍然需要美國幫助,”他說,“美國要起的作用,就是堅守某種價值。這也是美國文化最重要的產物。當希拉里·克林頓(Hillary Clinton)談到互聯網自由時,我覺得真是太好了。”

這也是傳遞給美國人的一個信息。的確,我們有強大的軍力,但導彈的“硬實力”往往不及我們的理念的“軟實力”。在全世界倡導我們的價值觀,不可避免地會讓人指責我們虛偽、前後矛盾,但做一個前後不一致的民主與人權倡導者,總勝過始終如一地漠不關心。

我問艾未未,奧巴馬總統是否做了足夠的努力來提高人們對人權問題的關注。我希望白宮能聽到艾未未是如何回答這個問題的。

“我不知道他們在私下做了些什麼,”艾未未說,“但從表面上來看,他們做得還不夠。”

中國官方嘗試過授予艾未未榮譽,用顯赫的地位來買通他。他們也嘗試過把他投進監獄、對他進行罰款、並用棍棒狠狠地打他,以至於他需要接受緊急腦部手術。他們在絕望之中還曾懇求艾未未不要搗亂——但全都沒用。

當艾未未發佈了自己的一張裸照,把毛絨玩具當成遮羞布,用“草泥馬檔中央”諧音中文裡一句對中共中央的咒罵(更準確地說,是一句國罵)。而中共中央委員會又該做出何種反應呢?

比起被譴責,中國共產黨更厭惡的是被嘲笑,而幽默正是艾未未攻擊中共的代表性風格。其他異見人士如身在監獄的諾貝爾和平獎獲得者劉曉波,寫了大量有 關民主的雄辯文章,卻幾乎沒有吸引到普通的中國民眾。艾未未的藝術作品對很多人來說似乎也是無法理解的,但像草泥馬這樣的粗俗笑話能引起更多關注——也很 難被鎮壓。

“我覺得他們不知道怎樣對付像我這樣的人,”艾未未在接受採訪時說。“他們好像已經放棄管我了。”

中國共產黨面臨的一大麻煩是,55歲的艾未未是世界上最著名的藝術家之一。他的出身也和共產黨的革命戰爭緊密相連,其父母曾和中國新一屆最高領導人習近平的父母關係友好。

作為反抗政權的標誌性人物,艾未未的出現代表着中國的進步,反映出非官方的多元化正在興起。中國越來越讓我想起20世紀80年代早期的韓國和台灣,當時,受過教育的中產階級也是這樣開始一點一點地瓦解獨裁政權。

艾未未承認,中國確實出現了進步,他還說,他預計中國能在2020年之前實現民主——但他悲嘆現在已經太遲了。“他們已經浪費了整整一代的年輕人,”他說。

艾未未曾在紐約生活過十幾年,逐漸確立了他的藝術聲譽,而他的叛逆個性似乎也是在那些年中形成的。他在1993年回國,當時他36歲。最初他在政治上循規蹈矩,並參與了2008年北京奧運會宏偉的鳥巢體育場的設計。

2008年發生在西南省份四川省的大地震是讓他發生改變的一個因素。當時,許多校舍倒塌,學生家長抗議建築質量低劣,遭到了政府鎮壓。艾未未支持這些家長,開始要求政府更加公開。

他的對抗姿態惹怒了當局,他們毆打他,並強拆了他在上海的工作室。去年,政府又將他關押了近三個月。

當局仍禁止他出國,因此他無法出席自己正在華盛頓史密森尼博物館體系的赫什霍恩博物館(Hirshhorn Museum)舉行的藝術展。

這種壓力讓艾未未比以往任何時候都更強烈地感覺到,中國最大的問題之一便是專制政府。他不但沒有變得有所收斂,反而言論更加大膽。

“每一步,我都是被他們逼的,”他說。“我告訴他們,‘是你們創造了像我這樣的人。’”

出獄後,艾未未曾短暫地保持低調了一段時間,但隨後又恢復了他的政治惡作劇。為了監視他的舉動,當局在其工作室安裝了15個攝像頭。為了表示對此舉 的嘲弄,艾未未在互聯網上開設了名為“圍觀草場地”(weiweicam)的網站,播放從自己卧室傳出的畫面,這樣政府就能更密切地監視他了。

“他們幾乎是來求我把攝像頭關了,”他咧嘴笑着說。

我和他聊了很久。交談結束時,我問艾未未有沒有其他要說的。

“中國仍然需要美國幫助,”他說,“美國要起的作用,就是堅守某種價值。這也是美國文化最重要的產物。當希拉里·克林頓(Hillary Clinton)談到互聯網自由時,我覺得真是太好了。”

這也是傳遞給美國人的一個信息。的確,我們有強大的軍力,但導彈的“硬實力”往往不及我們的理念的“軟實力”。在全世界倡導我們的價值觀,不可避免地會讓人指責我們虛偽、前後矛盾,但做一個前後不一致的民主與人權倡導者,總勝過始終如一地漠不關心。

我問艾未未,奧巴馬總統是否做了足夠的努力來提高人們對人權問題的關注。我希望白宮能聽到艾未未是如何回答這個問題的。

“我不知道他們在私下做了些什麼,”艾未未說,“但從表面上來看,他們做得還不夠。”

Hitting China With Humor

January 01, 2013

Beijing

CHINA’S leaders have tried honoring Ai Weiwei and bribing him with the offer of high positions. They have tried jailing him, fining him and clubbing him so brutally that he needed emergency brain surgery. In desperation, they have even begged him to behave — and nothing works.

What is the Politburo to do with a superstar artist with a vast global audience like Ai (whose name is pronounced EYE Way-way), who makes a video of himself dancing “Gangnam style” with handcuffs — parodying the Chinese state — that quickly ends up with more than one million views on YouTube?

How should the Central Committee of the Communist Party react when Ai releases a nude self-portrait with a stuffed animal as a fig leaf? The caption was “grass-mud-horse in the center” — a homonym in Chinese for a vulgar curse against the Communist Party’s central leadership. Or, more precisely, against its mother.

One thing the party detests even more than being denounced is being mocked, and humor is the signature element of Ai’s assaults. Other dissidents, like the great writer Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize winner now in prison, write eloquently of democracy but gain little traction among ordinary Chinese: Ai’s artistic work also seems incomprehensible to many people, but obscene jokes about grass-mud-horses can get more traction — and be difficult to quash.

“I think they don’t know how to handle someone like me,” Ai said in an interview. “They kind of give up managing me.”

One challenge for the Communist Party is that Ai, 55, is one of the world’s great artists. He also comes from a family with close ties to the Communist revolution, and his mother and father were friendly with the parents of China’s new top leader, Xi Jinping.

Ai’s emergence as an icon of resistance represents progress in China, a reflection of an unofficial pluralism that is gaining ground. China increasingly reminds me of South Korea or Taiwan in the early 1980s, when an educated middle class was nibbling away at dictatorship.

There is real improvement in China, Ai acknowledges, and he says that he expects democracy to reach China by 2020 — but he laments that it is already overdue. “They have wasted a whole generation of young people,” he said.

Ai’s irreverence seems shaped by the dozen years he spent in New York City burnishing his artistic reputation. He returned to China in 1993, at the age of 36, and initially behaved himself politically and played a role in designing the magnificent Bird’s Nest stadium for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

One factor that changed him was the terrible earthquake of 2008 in Sichuan Province in the southwest, when schools collapsed and the government clamped down on parents protesting shoddy construction. Ai backed the parents and began to demand more openness from the government.

Angered by his antagonism, the authorities had Ai beaten up and then destroyed his studio in Shanghai. Then last year the government detained him for nearly three months.

The authorities still block him from traveling abroad, so he is not able to attend a major exhibition of his work now under way at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington.

The pressure left Ai feeling more strongly than ever that one of China’s biggest problems is autocratic government. He became more outspoken, not less.

“At every step, they pushed me into it,” he said. “I told them, ‘You create people like me.’ ”

After briefly lying low after his imprisonment, Ai has resumed his political pranks. Mocking the authorities for installing 15 cameras to monitor his movements, he broadcast a public “weiweicam” on the Internet with a feed from his bedroom so the government could keep an even closer eye on him.

“They almost begged me to turn it off,” he said with a grin.

At the end of a long conversation, I asked Ai if he had anything else to say.

“China still needs help from the U.S.,” he said. “To insist on certain values, that is the role of the U.S. That is the most important product of American culture. When Hillary Clinton talks about Internet freedom, I think that’s really beautiful.”

There’s a message there for Americans. We have a powerful military, yes, but the “hard power” of missiles is often exceeded by our “soft power” of ideas. Speaking up for our values around the world invariably raises questions of hypocrisy and inconsistency, but it’s better to be an inconsistent advocate of democracy and human rights than to be a consistent advocate of nothing.

I hope the White House listens to how Ai responded when I asked if President Obama was doing enough to raise human rights concerns.

“I don’t know what they’re doing under the table,” Ai said. “But on the surface, they’re not doing enough.”

对政府持批评态度的中国艺术家艾未未表示,

Germany has asked Chinese artist Ai Weiwie to create the concept for the German pavilion in Venice but it is uncertain how the dissident -still under house arrest in China- will be able to travel to Italy.

"It is really an honor," Ai Weiwei told news agency dpa in Beijing, adding that he had accepted the invitation to create the concept for the German pavilion at the 55th Annual International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, which will take place from June 1 to November 24, 2013.

But whether the Chinese dissident will be able to travel to Venice is another question. He is still under house arrest in China. The project's curator, director of Frankfurt's Museum of Modern Art (MMK) Susanne Gaensheimer, asked Ai to design the concept such that it can be set up by other artists if need be, as it was completely unforeseeable whether or not he would be able to go himself, as Gaensheimer explained.

How others see Germany

"There are, of course, many, many great German artists who could design the pavilion," the curator said, "but I wanted to show that German's art scene is strongly influenced by an international network."

Christoph Schlingensief inspired Gaensheimer to transcend national identities

Gaensheimer said she hoped this would show how other people see Germany.

Christoph Schlingensief inspired Gaensheimer to transcend national identities

Gaensheimer said she hoped this would show how other people see Germany.

Aside from the Chinese artist and rights activist Ai, Gaensheimer also commissioned the Indian artist Dayanita Singh, Santu Mofokeng of South Africa and the German-French artist Romuald Karmakar. All four represent a different art genres, she said.

"Ai Weiwei will do something sculptural, Singh will present a slide projection, Mofokeng will exhibit photographs and Karmakar will do films."

Inspired by Schlingensief

Gaensheimer explained she got the idea to use international artists for the biennale from the late theater and film director Christoph Schlingensief.

She said he is the one who inspired her to "question" Germany's "national identity." Germany's art scene is made up of many different international elements. That's why Germany should not present itself as a "hermetic national unity" at the 55th biennale.

In the year 2011, Gaensheimer received the job to organize the German pavilion after Schlingensief, who had originally been given the job, died of lung cancer. Gaensheimer then completed the work with the help of his widow and some of his close friends. The pavilion received the Golden Lion.

But whether the Chinese dissident will be able to travel to Venice is another question. He is still under house arrest in China. The project's curator, director of Frankfurt's Museum of Modern Art (MMK) Susanne Gaensheimer, asked Ai to design the concept such that it can be set up by other artists if need be, as it was completely unforeseeable whether or not he would be able to go himself, as Gaensheimer explained.

How others see Germany

"There are, of course, many, many great German artists who could design the pavilion," the curator said, "but I wanted to show that German's art scene is strongly influenced by an international network."

Christoph Schlingensief inspired Gaensheimer to transcend national identities

Christoph Schlingensief inspired Gaensheimer to transcend national identitiesAside from the Chinese artist and rights activist Ai, Gaensheimer also commissioned the Indian artist Dayanita Singh, Santu Mofokeng of South Africa and the German-French artist Romuald Karmakar. All four represent a different art genres, she said.

"Ai Weiwei will do something sculptural, Singh will present a slide projection, Mofokeng will exhibit photographs and Karmakar will do films."

Inspired by Schlingensief

Gaensheimer explained she got the idea to use international artists for the biennale from the late theater and film director Christoph Schlingensief.

She said he is the one who inspired her to "question" Germany's "national identity." Germany's art scene is made up of many different international elements. That's why Germany should not present itself as a "hermetic national unity" at the 55th biennale.

In the year 2011, Gaensheimer received the job to organize the German pavilion after Schlingensief, who had originally been given the job, died of lung cancer. Gaensheimer then completed the work with the help of his widow and some of his close friends. The pavilion received the Golden Lion.

媒体看中国 | 2012.01.10

"艾未未:我们正处在改变权力结构的时代"

他说:"互联网是我们文明的一个产物,会将人转变成一个新的个人。尤其是当一个人没有任何背景,不掌握社会、经济或政治的权力,想要独立获得知识和信息时,互联网就为之提供了一个极好机会。此外,还可以在那里自由表达。

"这种规模在人类历史上还前所未有,互联网体现了彻底的革新,将会改变一切。我想,随之自然而然长大的年轻一代人将会更戏剧性地改变一切。"

在谈到被关押81天的感受时,艾未未说:"我晓得了专制者最怕什么。他们畏惧自由交流,畏惧超出其信条之上的一种感受能力。他们将任何与人的需求有关的表 达方式都看作犯罪,仅仅因为无法掌控。自从有了(被关押的)空间界限经验后,我就明白了一个艺术家的存在为什么对他们来说是危险的。

"他们为什么不能接受我的活动,我自由表达头脑之所想,有时用造型有时用行动,但总是在法律规定的范围内。为什么他们非要编造出一个假指控呢?他们为什么 不能与我敞开讨论呢?为什么不能告诉我何时可以还我自由?他们担心什么?……我开始觉察到,总是有个企图要毁掉个人生活和自由,仅仅籍此产生所谓权力。"

艾未未表示,"我已经明白,必须担起责任来,因为我发觉自己对中国许多人是重要的。因为很多人没有机会表达自己,对他们来说我就成了一种象征人物。"

"为没有权势者发声"

他说,"……凭感觉,名声会有助于我为那些永远没有权势的人发声。我觉得,要是我不利用自己的知名度为别人做点事,就是罪过。我不喜欢无动于衷地看着人们 如何通过简单地切断获得信息的渠道,剥夺这么多年轻人过上更好生活的可能性。将他们的智识引向邪路,让他们的生命变成荒漠,我觉得这是犯罪,要是不加以阻 止,就是罪恶的一部分。"

艾未未不赞成所谓"政治艺术家"的名称,他说,"以前我只是艺术家,后来就成了他们称作的政治艺术家。……当有人得知一位艺术家同事失踪时,至少得问问此人的下落,难道这就是政治吗?当我失踪时,几乎没有或许只有几个艺术家询问过。"

他还指出,"我们正处在一个改变权力结构的时代,阿拉伯国家和非洲的事件都表明这一点,而欧洲和中国的形势也是证明。我们在经历权力的倒退,比如华尔街,感到需要一个新的社会美学以及另一种行为。我还从未像现在这样有如此强烈的感觉。"

《柏林晨邮报》1月9日报道说,艾未未表示,只要当权者允许出境,他就先去柏林,接受柏林艺术大学为期三年的客座教授席位,最好6月23日就走,这个日子 是"取保候审"一年的结束日。该报说,"这位反对派艺术家是去年初被关押的一批律师、作家和维权活动家之一,当局怀疑他们将阿拉伯茉莉花革命的病菌引入中 国。"

2007:艾未未千人的卡塞爾作品是否會是虛張聲勢?德國之聲綜述:德國一些媒體今天引上海日報等中文報導,說中國北京的藝術家艾未未(詩人艾青之子)將帶領1001個人來參加6月12日至14日在卡塞爾舉行的第12屆“文獻藝術展”(Documenta)。他的構思是分成5組,每組200人,輪流上場。

2011.....中共 無法迴避: 艾未未事件是"中國政治/ 社會的惡質化"表現/

艾未未(詩人艾青之子)