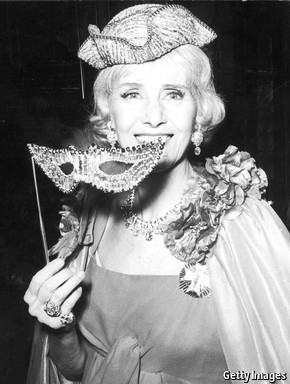

Clare Boothe Luce

A woman of substance

One of 20th-century America’s most remarkable women

Price of Fame: The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce. By Sylvia Jukes Morris.Random House; 735 pages; $35. Buy fromAmazon.com, Amazon.co.uk

BEAUTY was an asset Clare Boothe Luce used to her political (and financial) advantage. But so, too, were the other characteristics summed up by Sylvia Jukes Morris in this second and final part of her exhaustive biography of one of the most remarkable women of 20th-century America: “charm, humour, coquetry, intellect, ambition”. These brought her marriages to two wealthy men, two outspoken terms in the House of Representatives, an ambassadorship in Rome and an array of honours that culminated in the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Not bad for a woman born illegitimate in an unpromising part of New York.

Ms Morris’s first volume of Luce’s biography, published in 1997, was called “Rage for Fame: The Ascent of Clare Boothe Luce”. This concluding volume is just as pointedly titled. Luce’s first husband was an alcoholic, but he did at least give her money and father Ann, her only daughter. Her second marriage was to Henry Luce, the fabulously wealthy founder and owner of the Time-Life stable of magazines. Henry, who was already married with two young sons when he met Clare, admitted to a coup de foudre—a fate that befell an amazing number of men who came into her orbit. But Ann died in a car crash, her dissolute brother killed himself flying into the sea and the marriage to Henry, though it endured affairs on both sides, became a sexless ordeal of scant compatibility. In short, Luce’s political and social success came at a price: several suicide attempts (some probably genuine) and a reliance on sleeping pills and painkillers.But the package of characteristics, to which should be added a ferocious capacity for hard work, also brought much more: a career in journalism, complete with forays as a war correspondent in Europe in the 1940s; plays that were hits on Broadway; screenplays for Hollywood; and even, at the age of 54, the discovery of the joys of scuba-diving. Small wonder that in 1944, in her first term in Congress, the 41-year-old Luce was elected “Woman of the Year” by a poll of American newspaper editors, pushing Eleanor Roosevelt into a distant second place.

Fortunately, Ms Morris is not overwhelmed by the melodrama of Luce’s life. She had unparalleled access to her subject before Luce’s death in 1987 and to her papers (all 460,000 of them) in the Library of Congress. The result is a portrait of a woman gifted with intelligence and drive, but marred by narcissism and scarred by a constant sense of loneliness. There is a moving account of Luce’s conversion to Catholicism and a persuasive analysis of her role as ambassador to Rome in resolving the post-war status of Trieste.

As a Republican politician Luce was surely a forerunner of today’s “neocons”, a hawk in foreign policy and military affairs, but socially liberal (she was adamantly opposed to segregation). She enraged Democrats with her denunciation of Roosevelt’s New Deal and even accused the president of lying in order to take America into the second world war. Yet with her seductive beauty and charm she could count the Democrats’ Jack Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson as friends, adding them to a list that ran from Chiang Kai-shek and Winston Churchill to Noel Coward, Evelyn Waugh and Somerset Maugham.

As a female politician in the 1940s Luce was a rarity. Asked in her old age whether being a woman had disadvantaged her, she quipped, “I couldn’t possibly tell you. I have never been a man.” That question is less likely to be put to Hillary Clinton or other female stars of the modern American political scene. Nor, of course, is Mrs Clinton likely to have a Harper’scover story blaring: “Clare Boothe Luce: from Courtesan to Career Woman”. Luce’s characteristically witty reaction was that she would have preferred “from career woman to courtesan”.

'Price of Fame: The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce'

By SYLVIA JUKES MORRIS

Reviewed by MAUREEN DOWD

A second volume of the life of Clare Boothe Luce: playwright, screenwriter, editor, congresswoman, ambassador and presidential adviser.

| Hon. Clare Boothe Luce | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clare Boothe Luce in 1932, photo by Carl Van Vechten | |

| United States Ambassador to Italy | |

| In office May 4, 1953 – April 27, 1956 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Ellsworth Bunker |

| Succeeded by | James David Zellerbach |

| United States Ambassador to Brazil | |

| In office April 28, 1959 – May 1, 1959 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Ellis O. Briggs |

| Succeeded by | John M. Cabot |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Connecticut's 4th district | |

| In office January 3, 1943 – January 3, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Le Roy D. Downs |

| Succeeded by | John D. Lodge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ann Clare Boothe March 10, 1903 New York City, N.Y., U.S. |

| Died | October 9, 1987 (aged 84) Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | George Tuttle Brokaw (1923–1929, div.); 1 child Henry "Harry" Robinson Luce(1935–1967, his death) |

| Relations | Anna Clara Schneider & William Franklin Boothe (parents); David Franklin Boothe (brother) |

| Children | Ann Clare Brokaw (1924–1944) |

| Occupation | Editor, playwright, politician,journalist, diplomat |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Clare Boothe Luce (March 10, 1903[1][2] – October 9, 1987) was the first American woman appointed to a major ambassadorial post abroad. A versatile author, she is best known for her 1936 hit play The Women, which had an all-female cast. Her writings extended from drama and screen scenarios to fiction, journalism, and war reportage. She was the wife of Henry Luce, publisher of Time, Life, and Fortune.

Politically, Luce was a Republican, who became steadily more conservative in later life. In her youth, however, she briefly aligned herself with the Democratic liberalism of Franklin D. Roosevelt, as a protege of Bernard Baruch.[3] Although she was a strong supporter of the Anglo-American alliance in World War II, she remained outspokenly critical of the British presence in India.[4] A charismatic and forceful public speaker, especially after her conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1946, she campaigned for every Republican presidential candidate from Wendell Willkie to Ronald Reagan.

Title 普林斯頓散記

Author 林淑麗

Publisher 前衛出版社, 2005

ISBN 9578014759, 9789578014756

Length 174 pages

「追尋」,是邁向人生理想的一種自我實現,也是和心靈世界和解的一種方式。本書記述一位好勝的南台灣女子,在通過尖端科技的歷練之後,於?迴路轉之際,如何選擇重建人生的平衡點。它不僅是「從南台灣一路走來」的個人生涯記錄,也以「望鄉」的心情,藉?身歷其境的體驗,抽絲剝繭,將「人」和某些抽象名詞的關係一一解套,期盼突破隔離人類種族、地域、歷史、文化的沉默「冷牆」,尋求未來世紀人類自省、反思與救贖的可能。

本書適合於:(1)於親情、成長、死亡等人生問題尋求方向、支柱的讀者;(2)關懷文明的未來,尋求了解現代文明現象,對人的處境具有悲憫心的讀者;(3)企圖探討國際互動、兩岸問題及台灣經驗的新視野的讀者。

林淑麗簡歷

台灣大學化工學士,美國羅傑斯大學化工碩士;曾任光纖通訊半導體元件研究工程師,獲雜質活化技術專利一項。美國專業寫作訓練學校 Long Ridge Writers Group結業,作品曾刊於美國及台灣各大華文報及美國英文報;2005出版「普林斯頓散記」 (前衛出版社) ,曾受多位美國漢學者肯定及華文名家、讀者羣熱烈反響。於臺灣工研院「化工資訊與商情雜誌」TAITA專欄發表技術專文,並多次於美國主流社區及臺灣人社區演講及主持討論會。曾任北美臺灣工程師協會大紐約分會會長,現任該會理事及大紐約台大校友會理事。其他社區服務履歷:大紐約區海外台灣人筆會共同創始人及前理事,美國婦女會 CRANBURY分會理事;引介美國漢學界人士至僑社;引介英譯台灣文學作品至美國社區等。目前寫作以英文短評及回憶錄為主。

Brief Bio of Sue Shwu Lih Lin

-----

http://www.taiwanus.net/news/press/2011/201104011900031488.htm

紐澤西孟郡圖書館總部2011年度中文講座

林淑麗主講

「從阿拉伯的勞倫斯看中東熱」

紐澤西孟郡 (Monmouth County) 圖書館總部每年舉辦兩次中文演講,這是該館鼓勵多元文化閱讀的傳統之一。 2011首次演講於 三月二十六日下午二時至四時半舉行,主題為「從阿拉伯的勞倫斯看中東熱」,由「普林斯頓散記」作者林淑麗 (現任大紐約區台灣工程師協會會長) 主講。

林女士向聽眾推薦「智慧七柱」(台灣馬可孛羅文化出版) 為主要參考書,它由蔡憫生譯自英文本“Seven Pillar of Wisdom”,其作者 T. E. Lawrence 即1962 奧斯卡最佳影片「阿拉伯的勞倫斯」所描述的伝奇人物。他在第一次大戰期間代表英國深入中東阿拉伯人陣營,以游擊戰策略協助他們推翻奧圖曼的統治,此乃英法俄美等聯盟致勝的關鍵戰役之一。該書被列為沙漠戰略的參考書,不但對阿拉伯部落文化及中東地理景觀有令人稱奇的描述,並為英國與阿拉伯戰時的微妙伙伴關係留下寶貴的紀錄。文豪蕭伯納稱之為難以匹敵的舉世傑作。

林女士準備了二十五張圖文並茂的Power Point slides, 以看圖說故事的方式進行講解。 她說九一一事件的發生及二OO三年美國出兵伊拉克,使得世人不得不面對回教世界的歷史與現況。據Institute ofInternational Education

,二OO七年赴中東各國留學的美國大學生增至三千三百九十九人,是 二OO二年的六倍。從十字軍東征以降,西方與中東世界的衝突並非無歷史脈絡可循;本專題以勞倫斯的沙漠冒險為經,以歷史為緯,簡述第一次大戰期間阿拉伯人為建國所作的奮鬥,及戰後發現被欺騙的史實,它導至現代中東回教國對西方介入其內部事務常採高度懷疑的態度。1915年底,英國在Dardanelles 及Kut的兩次戰役失利,迫於戰略考量,對阿拉伯獨立陣營的領導者胡笙教主(Grand Sherif Hussein) 作出戰勝後的領土承諾,卻於1916年初與法國簽下大背其道的密約 (Sykes-Picot Agreement)。戰後的巴黎合約及多國協定(League of Nations Mandate) 將阿拉伯半島之外的中東版圖交由英美瓜分,後來經過勞倫斯的努力及邱吉爾的贊助,才在開羅會議 (1921年) 作出讓步,始有伊拉克約旦兩國的誕生,其餘屬地則遲至第二次世界大戰後才陸續獨立。

演講的第二部分,林淑麗略述以色列建國,並回顧回教的分裂。 她綜合美國中東策略的幾項考量,包括原油供應、地理政治因素、 恐佈份子操作 及以色列巴勒斯坦之爭等。回教世界自第七世紀起即分成遜尼派 (Sunni) 及什葉派 (Shiah),後者雖為少數,對涉及以色列及西方的政策傾向極端主義。中東世界除了Gulf產油國之外,普遍的貧窮,加上戰亂頻繁,及被侵略欺騙的歷史記憶,使人民容易受煽動, 甚至成為欲摧毀西方基督文明的恐怖份子。

林女士亦提出一些正面思考:她舉例說,公元十世紀前後,在歐洲到處搶劫的維金人,終於漸漸昄依基督教,建立了文明社會; 退後一步前進兩步,才能有進化的大歷史。 最近在北非及中東多國的抗爭運動,可看出令人鼓舞的現象:以埃及為例,它的非武力革命所以能成功,應得力於現代電子互聯網號召、獨立軍隊保護示威民眾,及全球改革運動人士的長期互授策略。這些發展該值得珍惜重視。她又說,中東的歷史、大自然及宗教三方面確是人類共同的挑戰,但何嘗不是各方人材的机會,亦期待有勞倫斯之類的英雄的出現。第一次大戰的時空條伴雖與二十一世紀的今日很不同,但是勞倫斯的沙漠傳奇仍提供現代人無限的想像。

歷時八十分鐘的演講在休息片刻後開始發問。孟郡有不少高科技業的華人,這天到場的聽衆大多充滿好奇,也有人已事先翻看些資料,整個討論的面向極廣,有相益得彰的效果。

沒有留言:

張貼留言