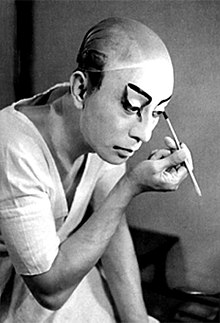

- Domon in 1948

- http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2017/04/16/arts/ken-domon-artistry-real-life/#.WPP9FIh97IU

-

Ken Domon - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ken_DomonKen Domon (土門 拳, Domon Ken, 25 October 1909 – 15 September 1990) is one of the most renowned Japanese photographers of the 20th century. He is most ...

- Born: October 25, 1909, Sakata, Yamagata Prefecture, JapanDied: September 15, 1990, Tokyo, Japan

Ken Domon and the artistry of real life

BY MARTIN LAFLAMME

SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMESBy 1957, photographer Ken Domon had reached the peak of his creative powers. A picture taken that year in Hiroshima, which he was visiting for the first time to chronicle the lingering effect of the bomb, shows him supremely confident: ram-rod straight on a stool, tripod in one hand, he casts a sideway glance at the viewer. His brow is lightly furrowed; his lips display a slight pout reminiscent of a kabuki actor adopting a mie pose. What we see is an intense, tenacious and uncompromising mind.Two years later, Domon suffered the first of three brain hemorrhages that marked the beginning of a long, slow and painful decline. In an image from 1979, on a photo shoot near Nara, he is in a wheelchair, his shoulders slumped, his cheeks a bit hollow. We can still notice a glimmer of passion in his eyes, but his gaze is distant. Not long after that, he was back in the hospital, in the coma in which he remained until his death in 1990.Domon was a prolific artist who produced almost 70,000 photographs over a career that spanned more than four decades. And yet, much like Japanese photography as a whole, he was until recently almost completely unknown outside his homeland. In fact, the first museum exhibition entirely dedicated to his work was organized only last year, in Rome, and the accompanying catalogue, which will be published in English by Skira in June, is the first full monograph on his life and work to appear in that language. Late in coming, this recognition is long overdue.The son of a nurse and office worker, Domon was born in 1909, in the city of Sakata, on Japan’s snowy northeastern coast of Yamagata Prefecture, where the Ken Domon Museum of Photography is located today. He moved to Tokyo when he was 7 and while still in his teens, he developed a passion for painting — he exhibited his first canvas at 17 and promptly sold it for ¥30. However, he never succeeded in making a living out of painting, so in 1933 he followed his mother’s advice and joined a photography studio as an apprentice. This turned out to be a great move: two years later, he was working for Yonosuke Natori, the founder of Nippon Kobo, one of the most important publishing agencies of that era, and an influential force in the development of photojournalism in Japan. Domon had found his calling.The period that followed the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, when Domon came of age, was a time of great social ferment, when Japan was undergoing rapid and, at times, chaotic change. Artists engaged in bold experiments and moved beyond the mere imitation of Western modes of expression that had previously been prevalent. Graphic magazines and photo supplements were established, and these helped disseminate a new aesthetics. By the early 1930s, photographers were also learning how to use their cameras to critically draw attention to the country’s social ills.By the later years of that decade, however, the atmosphere had changed. With the Pacific War in full swing, censorship became stifling. Like many of his peers, Domon produced propaganda images for a while, but he became disillusioned, even critical of the government’s attitude toward art, and he struggled to find ways to do work that remained meaningful.In 1939, he visited Nara’s Muroji Temple for the first time — he would return over and over again — and this became a turning point. In the words of Rossella Menegazzo, a professor at the University of Milan and the co-curator of the Rome exhibition as well as the co-editor of the catalogue, it marked the beginning of “the greatest effort of reportage of his life.” Domon then spent much of the following five years photographing Japan’s cultural and architectural heritage. His widely hailed series on bunraku (puppet theater), which by 1943 totaled 7,000 images, dates from that period.The postwar years, particularly the 1950s, marked the climax of Domon’s influence as a photographer and public intellectual. He went freelance in 1945 and began collaborating with a broad range of publications. He also became a judge for amateur competitions, wrote essays and became one of the leading exponents of a social-realist approach to photography.In an email interview, Menegazzo explained that what mattered most for Domon was “to show the pure reality” in front of his eyes.“In a society profoundly scarred by war and defeat, Domon refused to make beautiful photos,” she added. “This is particularly evident in the Hiroshima series, which was shocking and therefore criticized by many, but it also significantly changed the consciousness of people in Japan after the war.”In those days, there were few commercial galleries focusing on photography and so the main medium to spread knowledge of one’s work was through books. Some of Domon’s volumes sold as many as 100,000 copies.The “devil of photo-reportage,” as he came to be known, had little interest for the world beyond Japan. Except for a brief sojourn in China during the war years, he never traveled overseas. This partly explains why international recognition was so long in coming. But another reason is the sheer diversity of his work. As Menegazzo puts it, “It is not simple to assess the legacy of an artist who produced so much and continuously changed the subject of his work.”And so today, Domon is mostly remembered for his series, on Hiroshima, or on children, those of Koto Ward in Tokyo and of Chikuho in Kyushu, or for his portraits, smaller sub-sets of his oeuvre that are easier to digest.Domon did not purposefully aim to create beautiful images, but through patient and painstaking efforts, he captured the beauty of everyday life and culture in Japan. This alone ensures he will retain his place as one of the most important Japanese photographers of the postwar era.“Domon Ken: The Master of Japanese Realism” is published by Skira. For more information, visit www.skira.net/en/books/domon-ken-1- 鼻子骨折、腦震盪、掉了兩顆牙齒,可能需要做重建手術的鼻竇問題……這是被拖下飛機的69歲的杜成德(David Dao)醫生的現狀。「我爸爸遇到的事情,不應該發生在任何人身上,不管什麼情況」,杜醫生的女兒克里斯特爾說。

- 【王牌大律師出馬,聯航苦了!】遭到聯合航空無禮對待、粗暴拖下飛機的亞裔醫師陶大衛,已經委任專精傷害訴訟的芝加哥名律師迪米崔歐處理相關事務。根據官網介紹,他專精醫療過失、產品責任、空難賠償與商務訴訟,過去為當事人爭取到的和解金額超過10億美元

- 聯航UA事件背後的美國特權文化 拖人視頻網絡瘋傳 公司市值蒸發億萬 'We will work to...

根據越南報刊,聯航事件主角David Dao越南名為陶維英( Đào Duy Anh),中文報導似乎還沒發現。

來源:Bác Sĩ David Đào còn có tên Đào Duy Anh.

來源:Bác Sĩ David Đào còn có tên Đào Duy Anh.

沒有留言:

張貼留言